When a medication changes the way your heart beats - not by making it faster or slower, but by messing with its electrical timing - the consequences can be deadly. This isn’t science fiction. It’s a real, documented risk tied to something called QT prolongation. And it’s happening more often than most people realize.

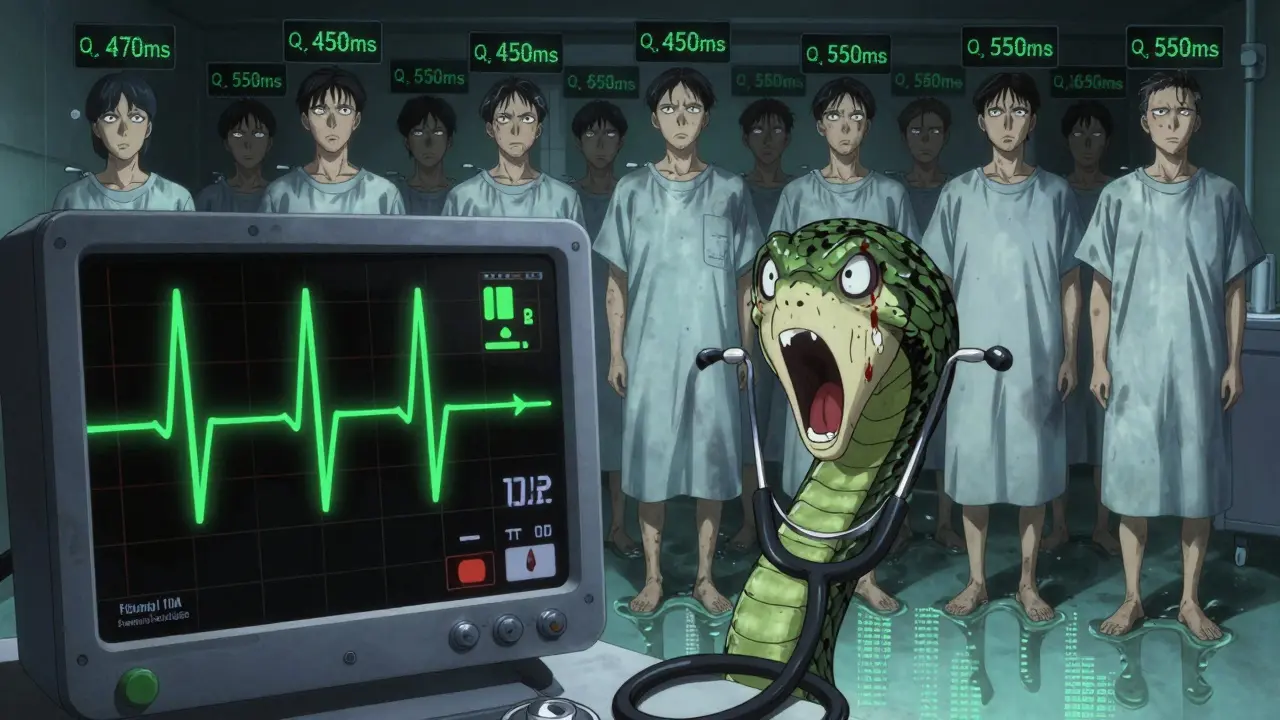

QT prolongation means the heart’s ventricles are taking longer than normal to recharge after each beat. On an ECG, that shows up as a longer QT interval. At first glance, it might look like just a number on a graph. But when that number climbs past 500 milliseconds, or jumps more than 60 ms from your baseline, it’s a red flag. It means your heart is sitting in a dangerous electrical state - one that can spiral into torsades de pointes, a chaotic, life-threatening rhythm that can turn into sudden cardiac arrest.

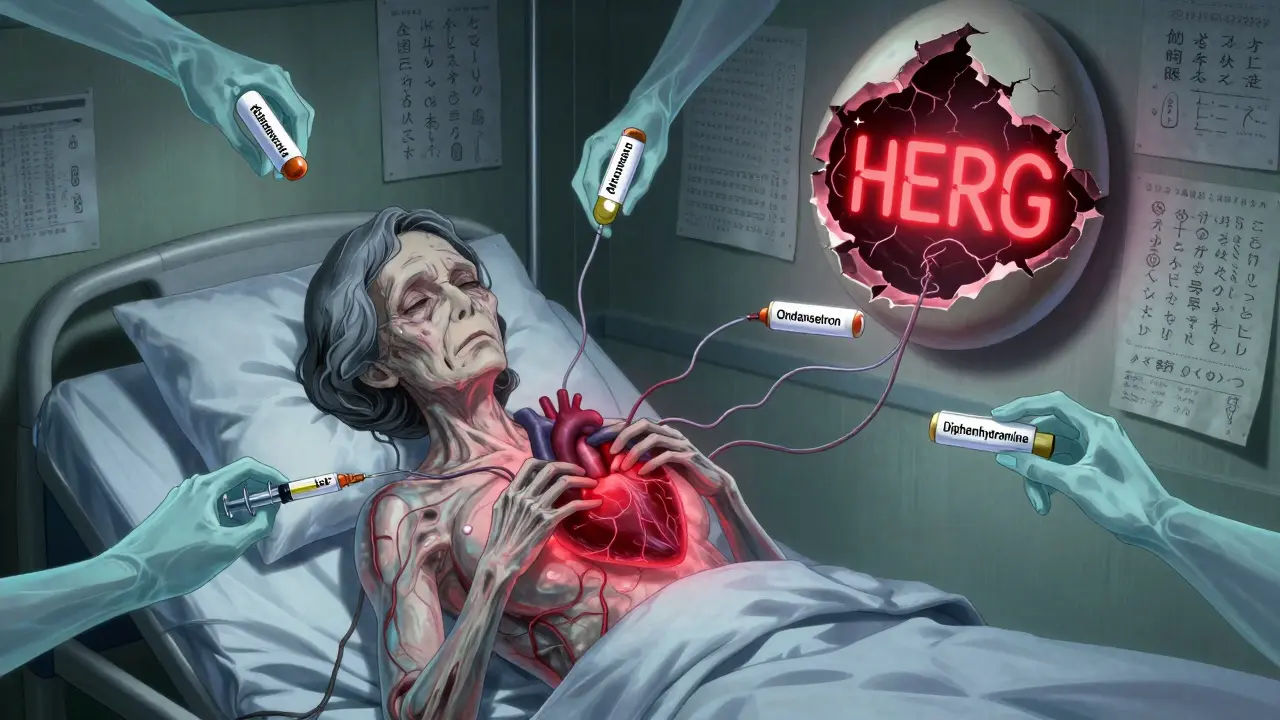

Here’s the twist: you don’t need to be on heart medicine to be at risk. In fact, some of the most common drugs prescribed for everyday problems are the ones doing the damage. Antibiotics like clarithromycin and azithromycin, antifungals like fluconazole, anti-nausea pills like ondansetron, and even antidepressants like citalopram can all stretch out your QT interval. The FDA flagged 46 out of 205 tested drugs back in 2013 for this exact issue. By 2018, that list had ballooned to 223 medications with known, possible, or conditional risk - and it’s still growing.

Why Does This Happen? The hERG Channel Explained

The root of the problem lies in a single protein channel in your heart cells called hERG. This channel controls the flow of potassium out of the cell during repolarization - the phase where the heart resets after contracting. When a drug blocks this channel, potassium can’t leave fast enough. The result? The heart muscle stays electrically charged longer than it should. That’s QT prolongation.

It’s not always intentional. Antiarrhythmic drugs like sotalol and dofetilide are designed to prolong repolarization to stop abnormal rhythms. But even they can trigger the very arrhythmia they’re meant to treat. Sotalol, for example, causes torsades in 2-5% of patients. Amiodarone, another Class III drug, does too - but less often, around 0.7-3%. Why? Because amiodarone doesn’t just block hERG. It also affects sodium and calcium channels, which somehow stabilizes the rhythm. It’s a balancing act - and one that’s easy to mess up.

Non-cardiac drugs are trickier. They weren’t built to touch the heart’s electrical system. But because hERG is shaped like a funnel, many unrelated chemicals - from antipsychotics like haloperidol to pain meds like methadone - slip right in. Ziprasidone, an antipsychotic, carries a black box warning for ventricular arrhythmia. Methadone? Doses over 100 mg daily are a known trigger. And citalopram? The FDA capped it at 40 mg a day (20 mg if you’re over 60) because higher doses reliably stretch the QT interval.

Who’s Most at Risk?

It’s not just about the drug. It’s about you.

Women make up about 70% of documented torsades cases. Why? Hormonal differences. Estrogen slows down repolarization. Testosterone speeds it up. That means women’s hearts naturally have longer QT intervals - and are more vulnerable when a drug pushes them further. The risk spikes even more after childbirth.

Age matters too. People over 65 have slower drug clearance. Their kidneys and liver don’t flush out meds as fast. That means higher blood levels. Higher levels = longer QT. And if you’re already on multiple QT-prolonging drugs? That’s a recipe for disaster. One study found 68% of TdP cases involved two or more of these drugs. A 65-year-old woman on ondansetron for nausea and azithromycin for a sinus infection? Her QTc can jump from 440 ms to 530 ms in under 24 hours. That’s not rare. It’s reported.

Electrolytes are another silent player. Low potassium, low magnesium, low calcium - all of these make the heart even more sensitive to QT-prolonging drugs. A simple blood test can catch this. But it’s often overlooked.

And then there’s genetics. About 30% of drug-induced torsades cases happen in people with subtle, undiagnosed mutations in the hERG gene. These aren’t the rare, inherited long QT syndromes. They’re common variants that only cause trouble when a drug is added. That’s why two people on the same dose of the same drug can have wildly different outcomes.

Which Drugs Are the Worst?

Not all QT-prolonging drugs are created equal. Here’s how they stack up:

| Drug Class | Examples | Typical QTc Increase | TdP Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class Ia Antiarrhythmics | Quinidine, Procainamide | 20-50 ms | High (up to 6%) |

| Class III Antiarrhythmics | Sotalol, Dofetilide, Ibutilide | 15-40 ms | High (2-5%) |

| Antibiotics | Erythromycin, Clarithromycin, Moxifloxacin | 10-25 ms | Moderate to High (especially with CYP3A4 inhibitors) |

| Antipsychotics | Haloperidol, Ziprasidone, Thioridazine | 10-30 ms | Moderate (Ziprasidone: black box warning) |

| Antiemetics | Ondansetron, Domperidone | 5-15 ms | Moderate (high risk when combined) |

| Antidepressants | Citalopram, Escitalopram, Fluoxetine | 5-20 ms (dose-dependent) | Low to Moderate (FDA limits citalopram to 40 mg/day) |

| Opioid Analgesics | Methadone | 10-40 ms | High (dose >100 mg/day) |

Notice how even “low-risk” drugs like ondansetron become dangerous when stacked. A 2020 FDA analysis found ondansetron was involved in 42% of TdP cases - not because it’s the strongest, but because it’s used so often. Same with azithromycin. It’s a common go-to for respiratory infections. But when paired with another QT-prolonger? The risk multiplies.

What Should You Do?

Here’s the practical side. If you’re prescribed any new medication - especially if you’re over 65, female, on multiple drugs, or have heart disease - ask these questions:

- Is this drug on the CredibleMeds list? (It’s free, updated quarterly, and used by hospitals worldwide.)

- Am I taking any other drugs that prolong QT? Even over-the-counter ones?

- Have my electrolytes been checked recently?

- Do I need a baseline ECG before starting?

The European Society of Cardiology recommends an ECG before starting high-risk drugs and another one 3-7 days later. That’s not optional for drugs like sotalol or methadone. It’s standard. And if your QTc hits 500 ms or jumps more than 60 ms from baseline? The drug should be stopped - unless there’s no alternative and the benefit outweighs the risk.

For people on long-term meds like methadone or antipsychotics, quarterly ECGs are wise. One 2021 study tracked 87 patients on methadone for opioid use disorder. None had torsades - because they got regular ECGs and kept doses under 100 mg. Simple. Effective.

The Bigger Picture: Regulation and Future Changes

The pharmaceutical industry is finally waking up. The CiPA initiative - launched in 2013 by the FDA, EMA, and Japan’s PMDA - is changing how new drugs are tested. Instead of just measuring QT prolongation, they now test how a drug affects multiple ion channels and use computer models to predict arrhythmia risk. Since 2016, 22 drugs have been dropped from development because of this. Each failure costs $2.6 billion. That’s a lot of pressure to get it right.

By January 2025, every new drug application must include CiPA data. That means fewer surprises down the line. But it also means existing drugs - the ones already on shelves - are still out there, quietly posing risks.

And it’s not just about new drugs. In November 2023, CredibleMeds added retatrutide, a new obesity drug, to its list after it showed 8.2 ms of QT prolongation in trials. It’s not a big jump - but it’s enough to warrant caution, especially in people with other risk factors.

AI is coming too. A 2024 study showed a machine learning model could predict torsades risk with 89% accuracy by analyzing tiny, subtle changes in the ECG waveform - changes even experienced cardiologists might miss. That’s the future: smarter monitoring, not just more tests.

Right now, the best tool we have is awareness. Knowing which drugs are risky. Knowing who’s most vulnerable. Knowing when to ask for an ECG. Because QT prolongation doesn’t come with warning signs - until it’s too late.

Final Takeaway

QT prolongation isn’t a rare glitch. It’s a quiet, widespread threat hiding in plain sight - in your antibiotic, your antidepressant, your anti-nausea pill. The risk is low for any single person. But when you add up the millions of prescriptions written each year, the numbers add up to real deaths.

The solution isn’t to avoid all these meds. It’s to use them wisely. Ask your doctor: "Could this affect my heart’s rhythm?" Check your electrolytes. Avoid stacking drugs. Get an ECG if you’re high-risk. And if you’re on a drug with a known QT risk, don’t just assume it’s fine because you feel okay. Your heart’s rhythm doesn’t lie.

One ECG. One blood test. One conversation. That’s all it takes to prevent a tragedy.

What is a normal QTc interval?

A normal corrected QT interval (QTc) is under 450 ms for men and under 460 ms for women. Values above 500 ms are considered high risk for torsades de pointes. Any increase of more than 60 ms from your baseline ECG also raises concern, even if it’s still below 500 ms.

Can over-the-counter drugs cause QT prolongation?

Yes. Some antihistamines like diphenhydramine (Benadryl), certain cough syrups containing promethazine, and even some herbal supplements like licorice root can prolong the QT interval. It’s not just prescription meds - always check with your pharmacist before combining OTC drugs with your regular prescriptions.

Is QT prolongation always dangerous?

Not always. Many people have slightly prolonged QT intervals without any symptoms or events. The danger comes when multiple risk factors combine: a high-risk drug, low potassium, female sex, older age, or taking more than one QT-prolonging medication. That’s when the risk spikes from low to life-threatening.

How often should I get an ECG if I’m on a QT-prolonging drug?

For high-risk drugs like sotalol, methadone, or dofetilide, guidelines recommend a baseline ECG before starting, then another one 3-7 days after initiation or after any dose increase. For long-term use, quarterly monitoring is often advised. For lower-risk drugs, ECGs aren’t always needed unless you have other risk factors.

Can I still take citalopram if I’m concerned about QT prolongation?

Yes - but only at or below the FDA-recommended dose: 40 mg per day for adults under 60, and no more than 20 mg if you’re over 60. Avoid combining it with other QT-prolonging drugs. If you have a history of heart rhythm issues, your doctor may choose a different antidepressant like sertraline or escitalopram, which have lower risk profiles.

What should I do if I feel dizzy or have palpitations while on a QT-prolonging drug?

Stop taking the medication and seek medical attention immediately. Dizziness, skipped beats, or fainting could be early signs of torsades de pointes. Don’t wait. Call your doctor or go to the ER. An ECG can confirm if your QT interval is dangerously prolonged.

Kunal Majumder

January 10, 2026 AT 21:35Man, I had no idea my azithromycin could mess with my heart like that. I took it last winter for a bad cough and felt fine, but now I’m wondering if I got lucky or just didn’t hit the perfect storm. Gonna ask my doc next time I’m in.

Thanks for laying this out so clearly.

Aurora Memo

January 11, 2026 AT 22:20This is one of those posts that should be required reading for anyone on more than two prescriptions. I’m a nurse, and I’ve seen patients on three QT-prolonging drugs with low potassium and no ECGs. It’s terrifying how normalized it is.

Thank you for the CredibleMeds link - I’m printing that for my unit.

Ian Cheung

January 12, 2026 AT 06:39So let me get this straight - my antidepressant my grandma takes for anxiety and my kid’s nausea pill from the ER could team up like a villain duo in a bad superhero movie and send her heart into a glitchy loop

And we just hand these out like candy

Meanwhile the FDA’s still playing catch-up while people are dropping like flies from meds they didn’t even know were dangerous

It’s not a glitch it’s a system failure and nobody’s fixing it because profits > pulses

And don’t even get me started on how OTC stuff like Benadryl is basically a silent heart assassin

Wake up people

Christine Milne

January 13, 2026 AT 08:06While the concerns raised are not without merit, it is imperative to note that the overwhelming majority of patients who receive these medications do not experience adverse cardiac events. The statistical risk remains exceedingly low, and the proliferation of alarmist narratives undermines evidence-based clinical decision-making. Furthermore, the cited FDA data is often misinterpreted - many flagged drugs carry only conditional risk under specific metabolic conditions. This post, while well-intentioned, risks inciting unnecessary pharmacophobia among the lay public.

Bradford Beardall

January 15, 2026 AT 05:49As someone who grew up in India and now lives in the U.S., I’ve seen how differently meds are prescribed. Back home, my uncle got azithromycin for a cold and no one asked about his heart - and he’s 70. Here, my doctor asked for an ECG before giving me ondansetron. That’s the gap. We need global awareness.

Also - anyone else notice how the same drugs that cause QT issues in the West are still sold without warning in developing countries? That’s a public health crisis waiting to happen.

McCarthy Halverson

January 17, 2026 AT 03:54Check your potassium. Check your meds. Get an ECG if you’re over 65 or on more than one QT drug. That’s it.

Don’t overcomplicate it.

Your heart doesn’t care about your opinion - it just needs to beat right.

Ashlee Montgomery

January 18, 2026 AT 05:41It’s strange how we treat the body like a machine you can tweak with pills without consequences. We monitor blood sugar, cholesterol, even sleep cycles - but the electrical rhythm of the heart? Only when it’s too late.

Maybe the real issue isn’t the drugs. It’s that we’ve forgotten how delicate balance is.

neeraj maor

January 18, 2026 AT 15:21Who really controls the FDA? Big Pharma. The whole QT prolongation thing is a distraction. They want you scared of your meds so you’ll keep going back for more. The real cause of sudden cardiac death? 5G towers and the microchips in vaccines. Look at the data - the spike in arrhythmias started right after the rollout. Coincidence? I think not.

And why is CredibleMeds even a thing? Why isn’t this on every drug label? Because they don’t want you to know.

Wake up. They’re lying to you.

Ritwik Bose

January 18, 2026 AT 23:10Thank you for this comprehensive and deeply informative post. 🙏

As a healthcare professional from India, I can confirm that QT risk awareness remains critically low in our clinical settings. The absence of routine ECG screening for common prescriptions like azithromycin and ondansetron is alarming.

I have begun sharing this resource with my colleagues. Let us hope for systemic change - not just individual vigilance.