Pheochromocytoma Symptom Checker

Select Potential Symptoms:

Risk Assessment Results

Quick Takeaways

- Sudden, severe headaches or abdominal pain in a child may signal pheochromocytoma.

- Unexplained high blood pressure, especially with sweating or rapid heartbeat, is a red flag.

- Episodes of panic‑like symptoms (palpitations, trembling, pale skin) often come in bursts.

- Blood or urine tests for catecholamine metabolites confirm the diagnosis.

- Early surgical removal of the tumor usually cures the condition.

When a kid shows odd spikes in blood pressure or weird panic attacks, most parents think it’s stress or a cold. But a rare adrenal tumor called pheochromocytoma is a catecholamine‑producing tumor that arises from the adrenal medulla can be the hidden cause. Spotting the clues early can prevent dangerous spikes in blood pressure and save a child from a life‑threatening crisis.

What is Pheochromocytoma?

Pheochromocytoma is a tumor that usually forms in the adrenal gland, the small organ perched atop each kidney. The tumor cells release excess catecholamines-mainly adrenaline and noradrenaline-into the bloodstream. In children, this excess creates sudden bursts of symptoms that mimic anxiety, asthma, or a heart problem.

Why It Matters for Kids

Adults with pheochromocytoma often get diagnosed after a routine check‑up for high blood pressure. Kids, however, rarely have regular BP readings, so the tumor can stay hidden until a dramatic episode occurs. Uncontrolled hypertension can damage the brain, kidneys, and heart, leading to permanent issues. Early recognition not only prevents organ damage but also opens the door to a curative surgery.

Typical Signs and Symptoms

The classic triad-headache, sweating, and rapid heartbeat-looks the same in children, but the presentation can be more subtle or intermittent. Below is a quick reference of what to watch for.

| Sign / Symptom | How Often It Appears | Typical Age Range |

|---|---|---|

| Paroxysmal hypertension (sudden spikes) | 70‑80% | 5‑15 years |

| Headache - pounding or throbbing | 60‑70% | 4‑12 years |

| Profuse sweating (especially night sweats) | 55‑65% | 3‑10 years |

| Palpitations or racing heart | 50‑60% | 6‑14 years |

| Panic‑like attacks (trembling, pallor) | 45‑55% | 7‑13 years |

| Abdominal or flank pain | 30‑40% | 5‑12 years |

| Weight loss or failure to thrive | 20‑30% | 2‑8 years |

Notice that many of these signs come in bursts-minutes to hours-and then disappear. That on‑and‑off pattern is a tell‑tale sign that catecholamines are being released episodically.

When to suspect a Genetic Syndrome

About 30% of pediatric pheochromocytomas are linked to inherited conditions such as von Hippel‑Lindau disease, neurofibromatosis type1, or multiple endocrine neoplasia type2 (MEN‑2). Children with a family history of these syndromes, or who have other related tumors (e.g., retinal angiomas, neurofibromas), should be evaluated early. Genetic testing can pinpoint the mutation and guide both the child’s treatment and family counseling.

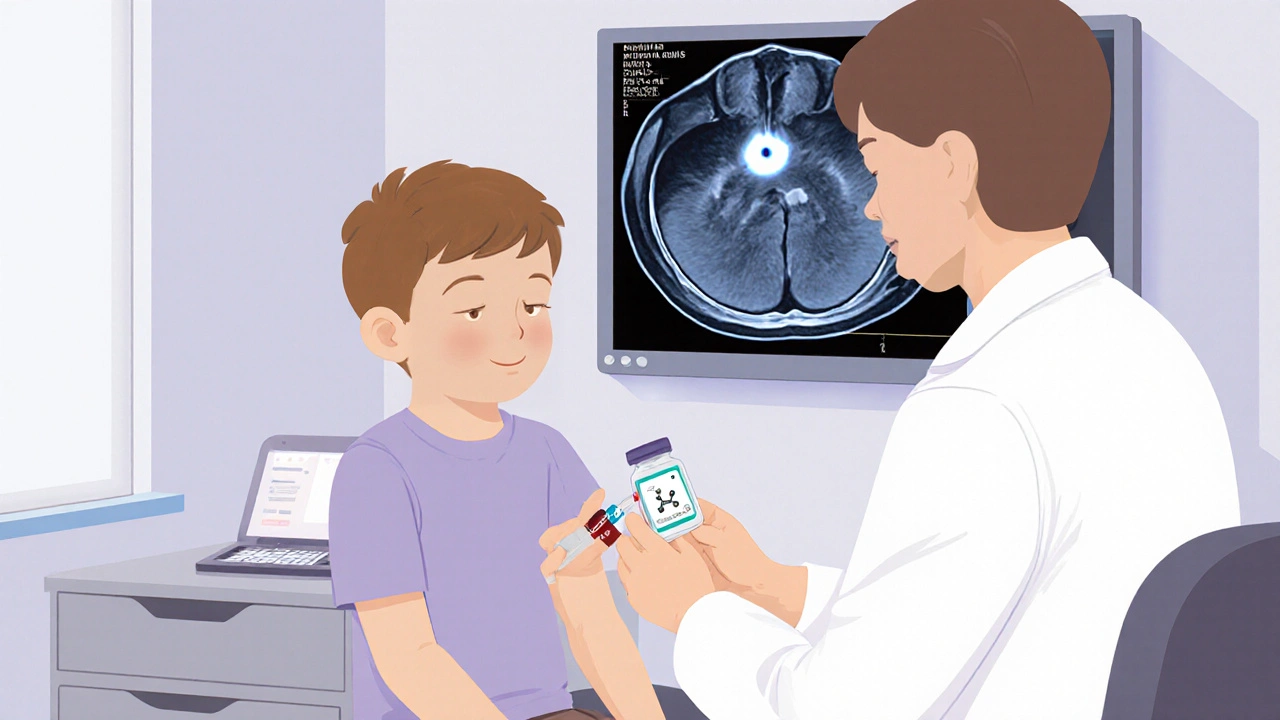

How Doctors Confirm the Diagnosis

1. Blood or urine testing - The most reliable markers are plasma free metanephrines or 24‑hour urinary fractionated metanephrines. Elevated levels (>2‑fold the upper limit) strongly suggest pheochromocytoma.

2. Imaging - Once biochemical proof is in hand, a CT scan or MRI of the abdomen pinpoints the tumor’s size and exact location. MRI is preferred for children to reduce radiation exposure.

3. MIBG scan (metaiodobenzylguanidine) - This nuclear medicine test helps locate extra‑adrenal or metastatic disease if the CT/MRI is inconclusive.

4. Genetic panel - If a hereditary syndrome is suspected, a targeted gene panel confirms the underlying mutation.

What to Do if You Spot the Warning Signs

Don’t wait for the next episode. Schedule an appointment with a pediatrician who can refer you to a pediatric endocrinologist or a pediatric surgeon. Bring a written log of blood pressure readings (if you have a home cuff), symptom timing, and any family history of tumors or genetic conditions.

Treatment Overview

Surgical removal of the tumor is the definitive cure. Before surgery, doctors use alpha‑blockade (e.g., phenoxybenzamine) for 10‑14 days to stabilize blood pressure and prevent intra‑operative spikes. Some centers add a beta‑blocker after the alpha block is effective to control heart rate.

Minimally invasive laparoscopic adrenalectomy has become the standard for most pediatric cases, offering quicker recovery and less pain. In rare cases where the tumor is malignant or spreads, additional chemotherapy or targeted therapy may be needed.

Long‑Term Follow‑Up

Even after a successful operation, about 10‑15% of children develop a new tumor later in life, especially those with a genetic syndrome. Annual blood pressure checks and periodic plasma metanephrine tests are advised for at least a decade after surgery.

Key Points for Parents and Caregivers

- Track any sudden episodes of high blood pressure, headaches, or sweating.

- Keep a symptom diary with dates, times, and triggers (like stress or certain foods).

- Ask the doctor about screening for catecholamine levels if the episodes are unexplained.

- If a tumor is found, surgery is usually curative; the pre‑op medication plan is crucial for safety.

- Stay vigilant for recurrence, especially if there’s a family history of related genetic conditions.

Frequently Asked Questions

How common is pheochromocytoma in children?

It’s rare-about 1 to 2 cases per million children per year-but because the symptoms can be life‑threatening, early recognition matters.

Can a regular blood pressure cuff detect the spikes?

Yes, if measured during an episode. Home cuffs that store readings are handy for capturing intermittent highs.

Are there any dietary restrictions before surgery?

Doctors usually advise a low‑tyramine diet (avoid aged cheese, cured meats, soy sauce) 24‑48 hours before surgery to minimize catecholamine release.

What genetic tests should be considered?

A panel that includes VHL, RET, NF1, SDHB, and SDHD genes covers the most common hereditary pheochromocytoma syndromes.

Is there a risk of the tumor coming back after removal?

Recurrence rates are low (under 5%) for sporadic cases but rise to 10‑15% in children with an inherited mutation, so lifelong follow‑up is recommended.

Paul Hill II

October 5, 2025 AT 13:32Great overview, especially the part about how the symptoms can come and go. Parents often miss those brief episodes because they think it’s just a bad day. Keeping a simple log of blood pressure spikes can be a game‑changer. The reminder about a low‑tyramine diet before surgery is spot‑on. Thanks for pulling the info together.

Stephanie Colony

October 8, 2025 AT 15:23Honestly, this whole “rare tumor” hype feels overblown – most kids just have anxiety. If you’re not into genetic testing, you’re fine.

Abigail Lynch

October 11, 2025 AT 17:13They don’t tell you that the pharma companies push catecholamine tests just to make a buck. Every new “symptom checker” is a surveillance tool. Trust your gut, not the lab. The real danger is the hidden agenda behind these articles.

David McClone

October 14, 2025 AT 19:04Oh sure, just slap a few meds on a kid and call it a day. Because nothing says ‘safety’ like a two‑week alpha‑blockade regimen. Sounds totally reasonable.

Jessica Romero

October 17, 2025 AT 20:55Reading through the surgical section reminded me how crucial pre‑operative alpha‑blockade is, especially in the pediatric population where cardiovascular stability can swing dramatically. The authors correctly note phenoxybenzamine as the classic agent, but many centers now favor selective long‑acting agents like doxazosin to minimize hypotension risk. It's also vital to monitor intravascular volume status; children often become volume‑depleted after prolonged catecholamine surges. Intra‑operative monitoring should include arterial line placement for beat‑to‑beat pressure readings, given the potential for abrupt hypertensive crises. Post‑op, patients need careful observation for hypoglycemia, as the abrupt removal of catecholamines can precipitate rebound insulin release. The recommendation of laparoscopic adrenalectomy aligns with current guidelines, yet open approaches remain the gold standard for large or invasive tumors. Genetic screening, as mentioned, not only informs family counseling but also guides surveillance protocols for future neoplasms. A multidisciplinary team-including endocrinology, anesthesia, surgery, and genetics-optimizes outcomes and reduces peri‑operative morbidity. Moreover, the article could expand on postoperative follow‑up intervals; annual plasma metanephrines for at least ten years are advised for hereditary cases. Patient education about the signs of recurrence, such as episodic headaches or sweating, empowers families to seek timely care. Nutritional counseling pre‑surgery, especially regarding the low‑tyramine diet, helps avoid intra‑operative catecholamine spikes triggered by high‑tyramine foods. The discussion of imaging wisely prefers MRI over CT to limit radiation exposure in children, which is a best‑practice point. I also appreciated the inclusion of MIBG scanning for extra‑adrenal disease, though newer PET tracers like 68Ga‑DOTATATE are gaining traction. Overall, the article balances layperson readability with sufficient clinical depth, making it a valuable resource for both caregivers and clinicians alike. Finally, documenting the exact timing of symptom episodes can aid future research on pheochromocytoma phenotypes.

Michele Radford

October 20, 2025 AT 22:46It’s disheartening that a condition affecting children still gets relegated to “rare” status, allowing healthcare systems to under‑fund research. We must demand more equitable allocation of resources to pediatric endocrine disorders. Ignoring early detection is a moral failure, not just a clinical oversight. Society should hold institutions accountable for these gaps.

Mangal DUTT Sharma

October 24, 2025 AT 00:37Thank you for such a thorough guide 😊! As a parent, I found the tip about keeping a blood pressure diary especially useful 📓. The part on low‑tyramine foods before surgery cleared up a lot of confusion 🍲. I’ll definitely share this with other families dealing with similar concerns. Keep up the great work 🙏.

Gracee Taylor

October 27, 2025 AT 01:27This article really bridges the gap between medical jargon and what everyday parents need to know. I appreciate the clear checklist for symptoms and the emphasis on early specialist referral. It’s comforting to see the focus on long‑term follow‑up for kids.

Leslie Woods

October 30, 2025 AT 03:18Keeping a symptom log is essential.

Manish Singh

November 2, 2025 AT 05:09i think a simple home bp cuff can catch those spikes early its cheap and easy to use. also talk to your doc about getting a metanephrine test if u see recurring episodes. dont delay because early detection can save a life.

Dipak Pawar

November 5, 2025 AT 07:00From a cultural perspective, the awareness of pheochromocytoma varies widely across regions, yet the clinical presentation remains universally similar. The article rightly highlights the importance of genetic counseling, which can be a sensitive topic in many families due to stigma associated with hereditary diseases. Incorporating community health workers in the screening process could improve early detection, especially in underserved areas. Moreover, dietary advice such as avoiding aged cheeses and cured meats should be tailored to local cuisines to ensure compliance. The recommendation for MRI over CT aligns with radiation‑sparing principles, a key consideration for children in low‑resource settings where CT machines are more prevalent. I also appreciate the mention of MIBG scans, though access can be limited; alternative functional imaging modalities may be needed. Finally, establishing a national registry for pediatric pheochromocytoma cases would facilitate research and improve outcomes globally.

Jonathan Alvarenga

November 8, 2025 AT 08:50Honestly, the article downplays the psychological impact on kids who live with unpredictable hypertensive episodes. Parents are left to navigate a maze of specialists without clear guidance on mental health support. The piece could have addressed coping strategies or counseling resources. Ignoring that side of the disease feels like an oversight.

Jim McDermott

November 11, 2025 AT 10:41I’ve seen a few cases where the classic triad was mistaken for anxiety, leading to delayed diagnosis. Consistent home monitoring made the difference in catching the spikes early. It’s also worth noting that some patients present with only abdominal pain, which can throw doctors off. Regular check‑ups are key.

Naomi Ho

November 14, 2025 AT 12:32For reliable testing, ask your doctor for plasma free metanephrines rather than just a urine test.