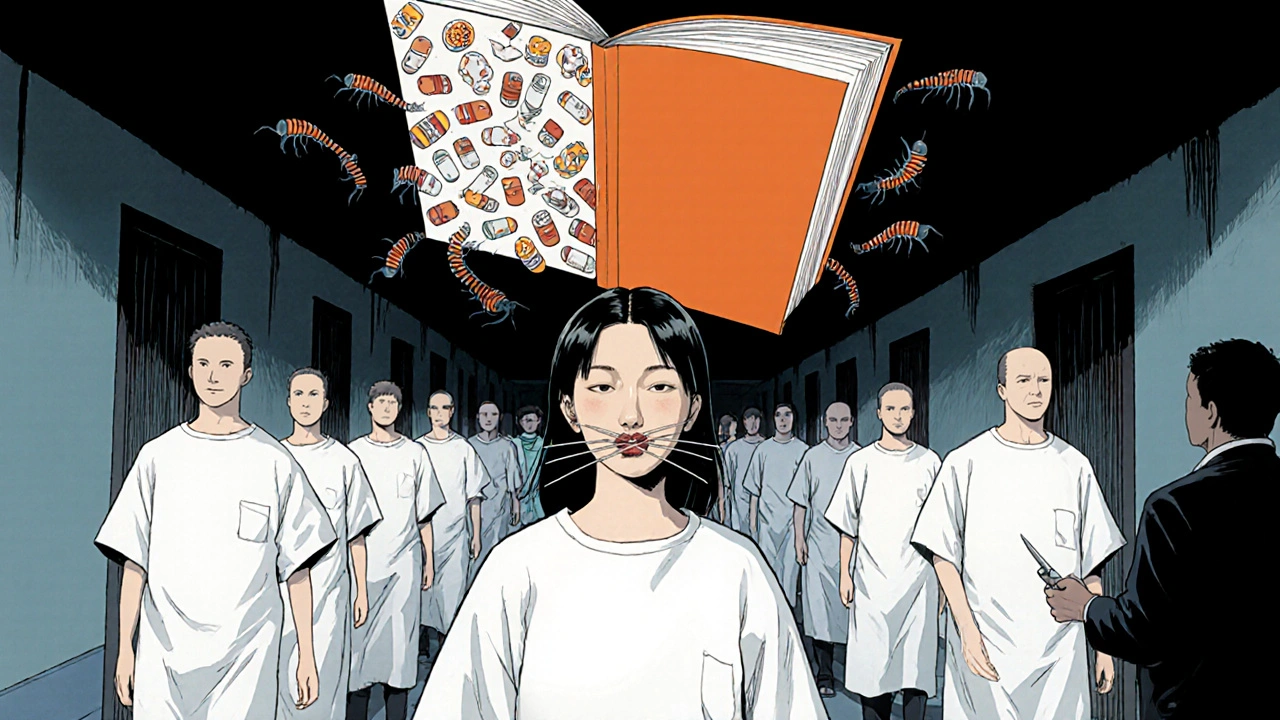

Generic drugs save patients and the healthcare system billions each year. In the U.S., 90.7% of all prescriptions are filled with generics - but that doesn’t mean every generic is safe to swap without question. Pharmacists aren’t just dispensers. They’re the last line of defense against hidden risks in medications that look identical on the bottle but behave differently inside the body.

Most generics work just fine. But when a patient’s condition suddenly worsens after switching brands - or when side effects appear out of nowhere - it’s not just bad luck. It’s a red flag. And pharmacists need to know exactly when to stop, ask, and intervene.

When a Generic Isn’t Really the Same

The FDA requires generics to match brand-name drugs in active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration. They must also prove bioequivalence: meaning the body absorbs the drug within 80-125% of the brand’s rate. Sounds strict? It is. But that 45% window - from 80% to 125% - is where problems hide.

For most drugs, that variation doesn’t matter. Take atorvastatin, the generic version of Lipitor. Studies show almost no difference in cholesterol reduction between brands. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI), even a 10% shift in absorption can mean the difference between control and crisis.

NTI drugs include levothyroxine, warfarin, phenytoin, digoxin, and tacrolimus. These are medications where the gap between too little and too much is razor-thin. A patient on levothyroxine might feel fine with a TSH of 2.1. Switch to a different generic manufacturer, and their TSH spikes to 8.7 - a sign of under-treatment. That’s not rare. Pharmacists report this pattern regularly.

Look-Alike, Sound-Alike: The Silent Killer

One of the most common errors isn’t about chemistry. It’s about confusion.

Oxycodone/acetaminophen and hydrocodone/acetaminophen look almost identical on labels. So do diltiazem CD and diltiazem ER. Patients don’t notice. But pharmacists do. And if a patient walks in with a new script for “hydrocodone” but the bottle says “oxycodone” - that’s a problem waiting to happen.

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices found that 14.3% of all generic medication errors involve look-alike or sound-alike names. These aren’t theoretical. In 2022, a patient in Ohio received a dose of oxycodone meant for someone else - because the pharmacy dispensed the wrong generic version. The patient died.

Pharmacists must check the manufacturer name on the bottle every single time. Don’t assume. Don’t trust the label alone. If the generic looks different from last month - even if the name is the same - verify it with the prescriber.

Extended-Release Formulas: The Hidden Trap

Not all generics are created equal - especially when it comes to how the drug is released over time.

Immediate-release pills dissolve quickly. Extended-release versions are designed to release slowly, keeping levels steady. But some generic manufacturers struggle to replicate these complex delivery systems. In 2020, FDA testing found that 7.2% of generic extended-release opioids failed dissolution tests - meaning the drug didn’t release as promised. That’s nearly seven times higher than immediate-release generics.

Patients on extended-release diltiazem, for example, might feel fine for weeks. Then, after a switch to a new generic, they start getting chest pain or dizziness. Why? The tablet isn’t releasing the drug properly. It’s either dumping too fast or not enough.

Pharmacists need to track which manufacturer supplied each batch. If a patient reports a change in how they feel - especially with controlled-release meds - check the manufacturer code. If it changed, flag it.

When to Flag: The Pharmacist’s Checklist

Here’s what to look for - and when to act:

- Therapeutic failure within 2-4 weeks of switching generics, especially with NTI drugs (levothyroxine, warfarin, etc.).

- Unexplained side effects - nausea, dizziness, fatigue - that weren’t there before the switch.

- Changes in lab values - TSH, INR, drug levels - that move outside the target range after a generic switch.

- Multiple switches - if a patient has been switched between three or more generic brands in a year, they’re at higher risk.

- Look-alike/sound-alike confusion - always double-check the manufacturer and product code on the label.

- Complex formulations - extended-release, transdermal patches, inhalers, injectables - these are more likely to have issues.

The FDA’s Orange Book is your best tool. Look up the therapeutic equivalence code. “AB” means it’s rated equivalent. “BX” means it’s not - and shouldn’t be substituted without a doctor’s approval. If you see a BX code, don’t dispense it unless the prescriber specifically wrote “Dispense as Written.”

What Happens When You Flag It

Pharmacists don’t just say “no.” They document, communicate, and follow up.

When you suspect a problematic generic:

- Ask the patient: “Have you noticed any changes since your last refill?”

- Check the manufacturer name and lot number on the bottle.

- Compare it to previous fills. Did the pill color, shape, or imprint change?

- Contact the prescriber. Say: “Patient reports [symptom]. Generic manufacturer changed. Could we return to the previous brand or confirm this substitution?”

- Report it. Use the FDA’s MedWatch system or ISMP’s reporting program. One report won’t change much. But 100 reports? That triggers an FDA investigation.

At the University of Florida, pharmacists started documenting manufacturer names in every patient’s file. Within six months, they identified a pattern: 68% of therapeutic failures could be traced back to a single manufacturer. That data led to a hospital-wide policy change.

Why This Matters - Real Patients, Real Consequences

One woman in Texas switched from one generic levothyroxine to another. She felt fine - until she started having heart palpitations. Her TSH was 10.5. She was in atrial fibrillation. She ended up in the ER. The new generic had a different filler - one that slowed absorption. It took three weeks to fix.

A man on warfarin switched generics and didn’t notice until he bruised easily and passed blood in his urine. His INR was 8.3 - dangerously high. His doctor later found the new generic had a different dissolution profile.

These aren’t outliers. A 2022 survey of 1,247 pharmacists found that 28.7% had seen patient harm linked to a generic switch. That’s nearly one in three.

And yet, 78% of patients still trust generics. They’re grateful for the savings. But trust shouldn’t mean silence. When patients say, “This one doesn’t feel right,” listen. It’s not in their head.

The Bigger Picture: Regulation Isn’t Enough

The FDA inspects over 2,000 facilities a year. They approved 97.8% of generic applications in 2022. But inspections don’t catch everything. Quality issues are often hidden - in foreign factories, in inconsistent raw materials, in rushed production lines.

India and China supply most of the world’s generic active ingredients. In 2022, the FDA found 1,247 quality issues across 387 foreign facilities. That’s one in three. And those problems don’t show up in bioequivalence studies - they show up in the patient’s body.

Even the FDA admits the system isn’t perfect. In 2023, they launched a new initiative to increase generic drug sampling by 40% over the next three years. But until then, pharmacists are the eyes on the ground.

What You Can Do Right Now

You don’t need a PhD to protect patients. Just attention.

- Always note the manufacturer on the prescription label - even if it’s the same as last time.

- When a patient complains about a generic, don’t dismiss it. Ask for details. When did it start? What changed?

- Use the Orange Book daily. Know which drugs are AB-rated and which are BX.

- Train your staff. Look-alike/sound-alike errors happen because no one double-checks.

- Report every suspected case. You’re not causing trouble. You’re preventing it.

Generics are essential. They make medicine affordable. But affordability shouldn’t come at the cost of safety. Pharmacists don’t just fill bottles. They protect lives. And sometimes, that means saying: “This one doesn’t belong here.”

Can generic drugs really be less effective than brand-name drugs?

Yes - but only in specific cases. Most generics work just as well. However, for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index - like levothyroxine, warfarin, or phenytoin - even small changes in how the body absorbs the drug can lead to treatment failure or toxicity. Bioequivalence standards allow up to a 20% difference in absorption, which can be dangerous for these medications. When patients report new symptoms after switching generics, it’s often not coincidence - it’s chemistry.

How do I know if a generic is rated as therapeutically equivalent?

Use the FDA’s Orange Book, available online. Look up the drug by name. Each entry has a therapeutic equivalence code. “AB” means it’s rated equivalent to the brand-name drug and can be substituted. “BX” means it’s not rated equivalent - often because of unresolved bioequivalence issues. Never substitute a BX-rated drug unless the prescriber specifically writes “Dispense as Written.”

What should I do if a patient says their generic medication isn’t working?

Don’t ignore it. First, confirm the manufacturer and lot number on the bottle. Compare it to previous fills - did the pill look different? Then, check if the patient recently switched manufacturers. For NTI drugs, consider ordering a lab test (like TSH or INR) to see if levels have changed. Contact the prescriber with your findings. In many cases, switching back to the original brand or manufacturer resolves the issue.

Are extended-release generics more likely to cause problems?

Yes. Extended-release formulations are harder to copy because they rely on complex delivery systems - not just active ingredients. FDA testing found that 7.2% of generic extended-release opioids failed dissolution testing, compared to just 1.1% of immediate-release versions. Drugs like diltiazem CD, metformin XR, and oxycodone ER are common culprits. If a patient reports sudden changes in effectiveness or side effects after switching to a generic extended-release version, investigate the manufacturer.

Why do some pharmacists avoid flagging generics?

Time pressure, fear of conflict with prescribers, and assumptions that “all generics are equal” are common reasons. Many pharmacists worry that questioning a generic will delay the patient’s care or upset the doctor. But the truth is, catching a bad generic early prevents hospitalizations. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists recommends documenting every substitution and following up with patients - not just as a best practice, but as a safety standard.

Is it legal to refuse to dispense a generic if I suspect it’s problematic?

Yes - if the prescription says “Dispense as Written” or if the generic is BX-rated. Even if the prescription allows substitution, pharmacists have a professional duty to ensure patient safety. If you believe a generic poses a risk - especially for NTI drugs - you can refuse to dispense it and contact the prescriber. Most states support this action under pharmacy practice laws. Your role isn’t just to fill prescriptions. It’s to prevent harm.

What Comes Next

The system is improving - slowly. The FDA’s new GDUFA III plan allocates over $1 billion to strengthen post-market surveillance. AI tools are being tested to detect patterns in adverse event reports. More guidance is being written for complex generics like inhalers and injectables.

But until those changes fully take effect, the burden falls on the pharmacist standing behind the counter. You’re not just counting pills. You’re watching for signs no algorithm can catch - a patient’s hesitation, a changed pill color, a lab result that doesn’t add up.

Flagging a problem generic isn’t about being difficult. It’s about being careful. And in pharmacy, careful is the only way to be.

Alyssa Torres

November 19, 2025 AT 15:45As a pharmacist in rural Texas, I’ve seen this too many times. A sweet elderly lady comes in crying because her ‘thyroid med’ suddenly made her heart race. She didn’t know the brand changed. We switched her back-she cried again, but this time from relief. Don’t underestimate how much patients notice. They just don’t always know how to explain it.

Summer Joy

November 21, 2025 AT 04:16OMG I CAN’T BELIEVE THIS IS STILL A THING?? 😭 Like, we’re letting foreign factories pump out pills that might as well be candy with a label?? The FDA is asleep at the wheel. Someone get this on 60 Minutes. #PharmaScandal

Aruna Urban Planner

November 21, 2025 AT 16:45The bioequivalence gap of 80-125% is statistically acceptable but clinically precarious for NTI drugs. The regulatory framework assumes homogeneity in patient pharmacokinetics, which is empirically invalid. In India, where 80% of API originates, batch-to-batch variability is often unmonitored due to infrastructural constraints. This is not a failure of pharmacists-it’s a systemic flaw in global supply chain governance.

Nicole Ziegler

November 22, 2025 AT 15:39Just had a patient tell me her generic diltiazem made her feel like she was on a rollercoaster. 😵💫 We checked the bottle-different manufacturer. Switched her back. She hugged me. Pharmacy is still magic sometimes.

Bharat Alasandi

November 23, 2025 AT 16:42Bro in India we make like 60% of the world’s generics and yeah sometimes the fillers change. But most of the time it’s just patients being extra. Like, if you feel weird after switching, maybe drink more water and chill? Not every pill is a life-or-death situation.

Kristi Bennardo

November 23, 2025 AT 22:30This post is dangerously misleading. The FDA has approved over 10,000 generic drugs with zero reported harm in 99.9% of cases. To suggest pharmacists should routinely challenge substitutions is to undermine the entire cost-saving infrastructure of modern healthcare. This is fearmongering dressed as vigilance.

Shiv Karan Singh

November 24, 2025 AT 15:04LOL you think generics are the problem? Try asking why brand-name Lipitor costs $300 a bottle while the generic is $4. It’s not the pill-it’s the system. Pharma companies push brand names to keep profits. Pharmacists are just pawns. Blame the CEOs, not the pills.

Ravi boy

November 25, 2025 AT 05:57my cousin in delhi works in a pharma lab and said sometimes the machines get dirty and the coating changes so the pill dissolves weird. not even a big deal. people just need to stop overthinking. also i typed this on my phone so sorry if i misspelled stuff

Matthew Karrs

November 25, 2025 AT 16:02They’re hiding the truth. The real issue? The FDA gets paid by the drug companies to approve their stuff. The bioequivalence tests? Fake. The labs? Owned by Big Pharma. That’s why no one talks about it. You think your ‘generic’ warfarin is safe? It’s a lottery. And you’re the sucker buying the ticket.

Russ Bergeman

November 26, 2025 AT 21:57Wait-so you’re saying pharmacists should be doing extra work? On top of filling 200 scripts a day? And then calling doctors? And documenting? And reporting? That’s not safety-that’s burnout. The system’s broken. Don’t blame the pharmacist. Blame the insurance companies that force switches.

Dana Oralkhan

November 28, 2025 AT 00:21I’ve worked in a clinic where patients couldn’t afford brand names. But I also saw one woman lose her job because her levothyroxine switch made her too tired to function. We kept a log. We flagged it. We didn’t blame her. We didn’t blame the pharmacy. We just kept asking: ‘What changed?’ Sometimes the answer is just a pill color. And that’s enough.

Jeremy Samuel

November 28, 2025 AT 22:41generics are fine. if you cant tell the difference between two pills then maybe you shouldnt be taking meds at all. also why do americans always think everything from india is trash? we make the best coffee too

Destiny Annamaria

November 29, 2025 AT 12:31Just got off the phone with my aunt in Ohio-she’s been on the same generic warfarin for 8 years. Last month they switched her brand and she started getting nosebleeds. Called her pharmacist-turned out the new one was BX-rated. They switched her back. She’s fine now. This isn’t conspiracy. It’s common sense. And it’s happening ALL THE TIME.